So you may not know, but I recently moved (again). Not down the street to a new house; not even back to the US because my student visa expired. No, I decided it made sense to pick up and fly south, to the country where everything can supposedly kill you and I knew next to no one: Australia. You might imagine that a couple of things may have slipped my mind in the process. Well, both have made their way back onto my radar, and will now be on yours.

The first, Friday at sunset the Jewish holiday of Passover began, marking the eight ensuing days of no grains and leavened products. It is an interesting holiday in that it actually touches on many salient issues in our contemporary world (e.g. slavery and freedom, injustice and inequality, agriculture and nature), and yet grasps firmly a set of archaic and at times illogical rules and restrictions. That said, an article I read this morning got me thinking about why we continue to follow these seemingly pointless traditions. The author noted, "I worry about making Passover too easy". And that's it; when something is easy, you don't need to think about it, take time to contemplate 'why am I doing this?', dwell on its relevance.

But this is not just a case for Passover (or the fasting holiday of Yom Kippur, either), but rather relates to many of the challenges that present themselves in our lives. So to me it is interesting that the annual Live Below the Line challenge* seems to coincide approximately with the completion of the holiday (and on occasion even overlaps). I almost missed the boat on having two food-related challenges over the course of two weeks, but luckily caught the oversight in time to begin living on AU$2 per day from May 2-6. Having taken part the last four years ($1.50 in the US and £1 in the UK), I can genuinely say it is a challenge, particularly considering I've always been in places with high costs of living (Washington, DC and Oxford are not known for their bargains...). But the challenge of it had made me think a bit more, empathize a bit more, pester all of you a bit more (donate!!). Tackling year five of the challenge in another new place has now made me research a bit more.

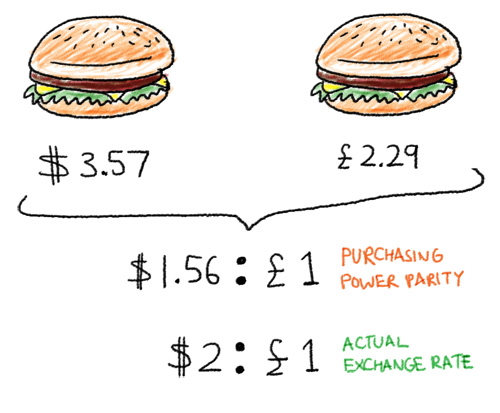

This brings me to the final topic of today's blog post: 'purchasing power parity'. Now, I am definitely no economist, so bear with me, but the concept of significance to understanding cost of living and affordability. It basically adjusts the price of good or bundle of goods to a common currency to compare against a baseline - for example, how many Big Macs could you buy in country X for US$1? The result is an idea of how expensive a place is to live (according to the Big Mac Index, we should consider moving to Venezuela for the greatest bang for our buck). And while it might explain why I now find the price of food in Australia to be a bit daunting (the dollar goes lessfar than in both the UK and the US), it also provides a rationale for those struggling in their home countries to migrate for work. My friend in Hong Kong pointed out the large number of Filipino and Indonesian women who come to the country for domestic work - not forever, just to send money home for a while. Price of goods is far greater in Hong Kong than either of the other two countries, but so are wages, much of which are sent back home where they can be stretched further.

Phew. Weighty stuff for a Monday morning (or Sunday evening). All of this is to emphasize the power of a little challenge to make us dwell a bit more on issues like hunger, poverty, and inequality. Stay tuned for more from my week Living Below, and don't forget to support the effort!

Further Reading:

*for some reason, it is not happening this year in the US or UK, so I have registered in Australia. This means that neither the Hunger Project nor the Rainforest Foundation, to which I have given in the past, will be on the receiving. But please do consider supporting the Oaktree Foundation working towards improving education!

1 comment:

It's common sense, but people don't often consider that you can calculate price indices at the local level too. States and cities have different price indices, or you can examine price differences between rural and urban areas of the same region. It's useful for plenty of policy applications and can relate to migration, transport and logistics, business competition, climate/disaster resilience, and more. There are patterns in how prices vary within countries and regions, and thinking about price indices at a local level can help us to better understand qualities of poverty and ability and more personal issues. For instance how gentrification pushes people away from a neighborhood as housing and food prices go up, or how segregation can lead to different neighborhood price levels in the same city and reinforce the segregation over time, or how temporary booms and busts and seasonal variation in work and prices can drive families around a country.

Also, when you think this way, it can be a mistake to assume everyone in the same place at the same time faces the same prices. People without a home, source of income, and significant possessions can often get by on the charity of others. Poor neighborhoods often provide for each other through sharing or a gift economy--for instance the remittances from a Filipina domestic worker might end up supporting more than her family, but the a couple other apartments on the block, which is part of why people go to such great lengths to earn more money, and why it's still a struggle to keep any of it.

Post a Comment